The old folk of Santo Stefano recount how a young man, who departed from the village to embark on a ship or to emigrate, would be taken by boat to the Calagrande to fill his eyes and memory with beauty.

History

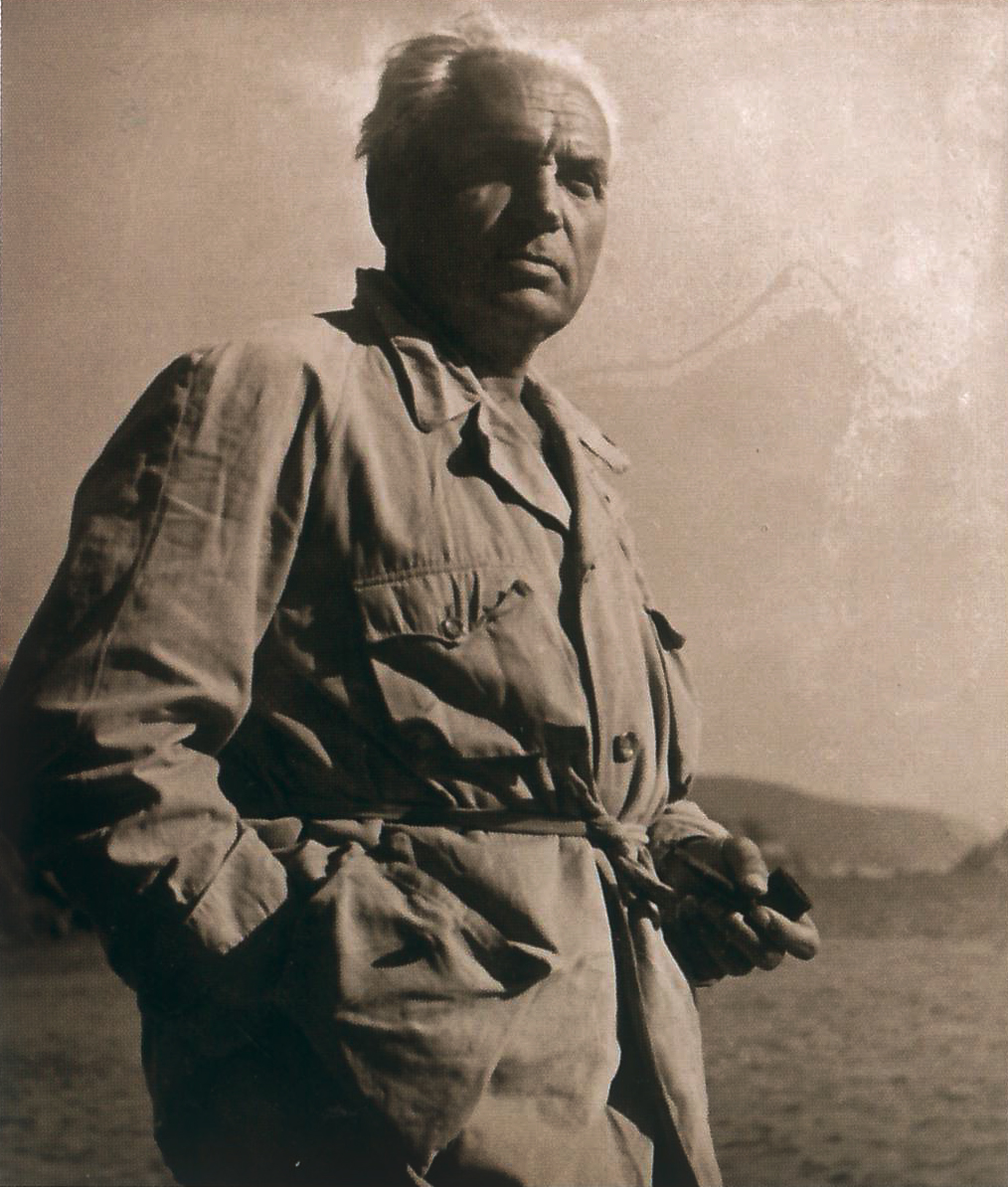

Arturo Osio 1890-1968

ARTURO OSIO

Marguerite Yourcenar, on the trail of the bas-relief of Antonianos, had occasion to meet Arturo Osio in Rome, whom she eminently portrayed in the biographical notes of her celebrated historical novel “Memoirs of Hadrian”:

The preceding paragraph appeared for the first time six years ago; meanwhile this bar-relief was acquired by a Roman banker, Arturo Osio, a whimsical man who probably would have stirred the imagination of Stendhal or of Balzac. Signor Osio has lavished upon this fair object the same solicitous attention that he gives to the animals on his property at the edge of Rome, where they run free in their natural state, and to the trees which he has planted by the thousand on his shore estate at Orbetello. A rare virtue, this last, for Stendhal was writing as early as 1828, “The Italians loathe trees” and what would he say today when real estate speculators, trying to pack more and more colossal apartment houses into Rome, are circumventing the city’s laws to protect its handsome umbrella pines? Their method is simply to kill the trees by injections of hot water. A rare luxury, too, though one which many a man of wealth could enjoy, is this landowner’s animation of woods and fields with creatures at full liberty, and that not for the pleasure of hunting them down, but for reconstituting a veritable Eden. The love for statues of classical antiquity, those great peaceful objects which seem so solid and yet are so easily destroyed, is an uncommon taste among private collectors in these agitated times, cut o from both past and future. The new possessor of the basrelief of Antonianos, acting on the advice of experts, has just had it cleaned by a specialist whose light, slow rubbing by hand has removed the rust and moisture stains from the marble and restored its soft glea, like that of alabaster or of ivory.

Marguerite Yourcenar – Memoirs of Hadrian

Edizioni Farrar Straus Giroux, New York (1954)

THE WHITE HOME (1935)

The Memories of Bernardino Osio

edizioni Centro Di, 2011

It was 1932 when Arturo Osio, who often hunted on Isola del Giglio, Albarese and Trappola with

his friends the Ponticellis, spotted our green cove from his boat. His enthusiasm was such that,

on learning that a small part of it was up for sale, he bought it.

ARTURO OSIO NEL MARE DI CALAGRANDE (1930)

MEMORIES

It must have been the summer of 1938 when I first went to Calagrande with my brothers, accompanied by Aunt Elisa. I vaguely remember a stopover in Rome at Uncle Arturo’s house in Via Molise. I recall the narrow-gauge steam train that ran from Orbetello to Porto Santo Stefano and then the motor boat that took us to Calagrande, piloted by the very experienced seaman, Olivo Lubrano, known as the Turk. The winding road with its panoramic views did not yet exist, and when the sea was stormy, one reached there overland on the back of a donkey. To us, children faring from misty Milan, it seemed as if we were landing in paradise. There were flowers and new scents, fruit with more intense flavours, sun, light, warmth and a crystal-clear sea, teeming with fish, that we had all to ourselves; the only happy inhabitants of Calagrande.

FRIENDS

Almost every Saturday afternoon, Uncle Arturo would arrive from Rome, invariably accompanied by entertaining friends, artists, writers and painters: Leo Longanesi, Amerigo Bartoli, Mino Maccari, the painter Carlo Socrate, the painter Achille Funi, Aldo Carpi, Franco Marinotti, Marco Ramperti, Bino Sanminiatelli, Curzio Malaparte, Luigi Barzini senior and junior, the Milanese poet Luigi Medici, Silvio d’Amico, a trench comrade in the Great War, and many others I do not recall.

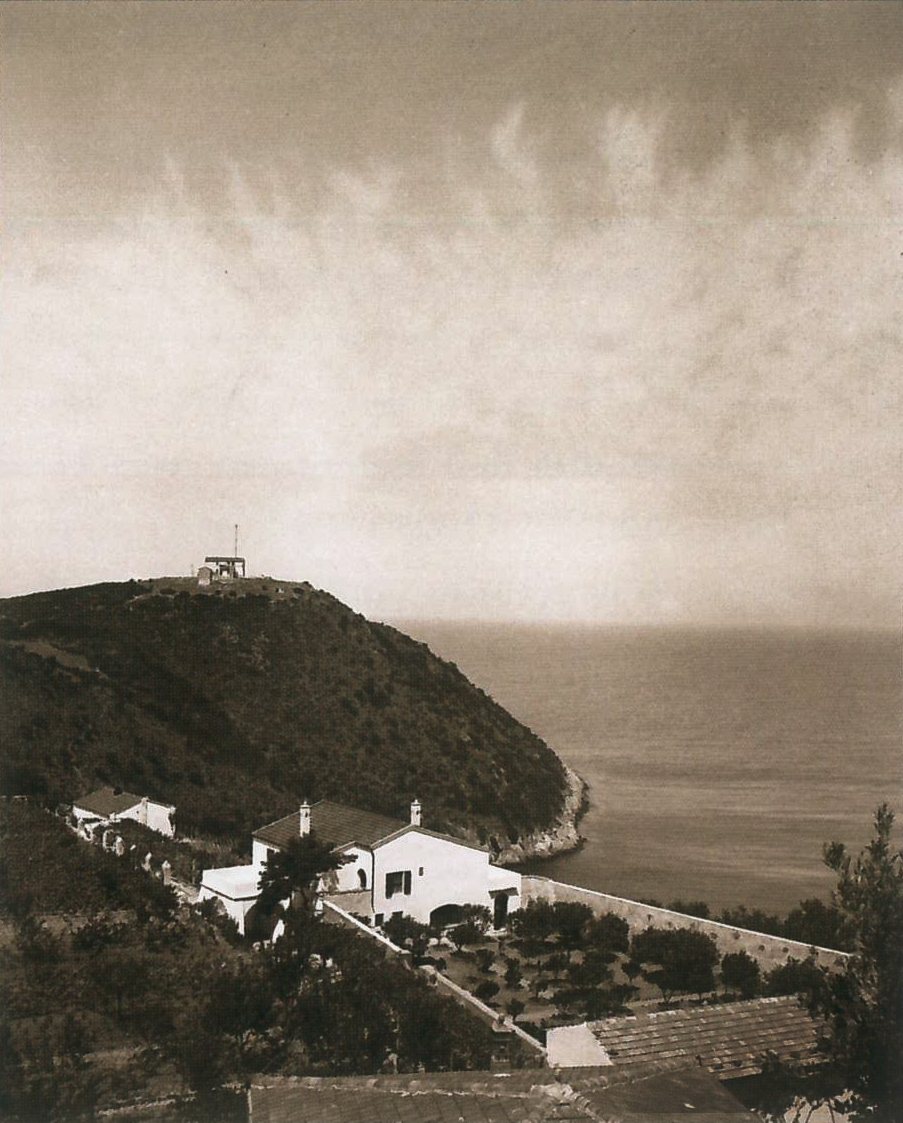

We sat under a pergola at sunset, but the greatest enjoyment lay not there, although they served us an exquisite fish of uncommon proportions. The greatest pleasure was in the place itself: the lush garden sloping down to the sea filled with citrus groves, vines, olive trees and cypresses, which occupied the whole of the cove and whose boundaries delineated the estate, so that other houses could not be seen except for, discreetly among the trees, the two – the red one and the white one- belonging to the owner of that little Mediterranean paradise, where nothing else disturbed the view except, perhaps, the traffic lights on a promontory; the only reminder of the modern world (but aren't traffic lights also a thing of the past?).

As the owner was a lover of antiquity, there were fragments of white statues all around us (but here a provocative lamp of the Pompeian type, which was lowered at certain gatherings in the city villa of that devotee of antiquity, did not hang over this table), and since our conversations spanned all manner of times and places, at a certain point I mused that, after all, the little less than two thousand years that separated us from the time of the Roman Empire did not constitute such a great distance, if at this hour and in this place, with little change in dress and language, one could have imagined oneself the subjects of the Caesars; the good Caesars or the bad Caesars, of Marcus Aurelius, of Septimius Severus, of Caracalla, of Heliogabalus.

Mario Praz – The Sense of Ruins

CALAGRANDE VISTA DAL MARE (CIRCA 1935)

PORTO SANTO STEFANO

THE WAR

In the summer of 1945, the bombardments, which had completely destroyed Porto Santo Stefano, because of its fuel depots for submarines, did not affect our cove, except for a few unexploded bombs that had fallen in the vineyards. On the other hand, Calagrande was invaded by evacuees who hailed from the village; the bank and the schools were in Casa Rossa. The chalet accommodated Olivo Lubrano's numerous families.

A few weeks before the liberation of Rome, uncle Arturo, by means of a friend’s car heading north, managed, between one bombing and another, to reach Calagrande and had a look at what was happening. He promptly returned to Rome, taking advantage of a truck, hired at enormous cost by Giannalisa Feltrinelli, who was fleeing to Rome with her husband Luigi Barzini junior and their three daughters, as Porto Santo Stefano had seen the heaviest bombardments in Italy since Cassino: they fled in the middle of the night with the headlights off, but were caught in Civitavecchia by raging bombardment and took cover among the mattresses and under the truck.

PROTECTION PLAN

Once the war was over, building fever swept across Argentario in the 1950s, when the Romans

discovered it. It was in those years that Arturo Osio, concerned about the imminent onslaught of

building speculation, together with the architect Porcinai, advocated the drafting of the first

landscape plan for Argentario and had the entire Calagrande included within the areas of

absolute protection.

VEDUTA DI CALAGRANDE (1930)

HORTULI HOSIANI

Uncle Arturo meanwhile kept coming for the weekend, always accompanied by interesting and amusing friends: I remember directors Mario Soldati and Roberto Rossellini, Louvre director Germain Bazin, Giovanni Urbani, Enzo Storoni, writer Marguerite Yourcenar, Flora Volpini, Paolo Monelli, Ercole Patti, Palma Bucarelli, painter Cesetti, Guido Carli, Mario Praz, sculptor Mimmo Spadini, and bookseller Rossetti. There was no lack of entertainment personalities: I remember Clara Calamai and Ingrid Bergman, Walter Chiari, Edmond Purdom and Linda Christian. Nor did the royals: those of Belgium, Paula and Albert and Empress Soraya of Persia.

ARTURO OSIO NEL MARE DI CALAGRANDE (1930)